*corrected/edited*

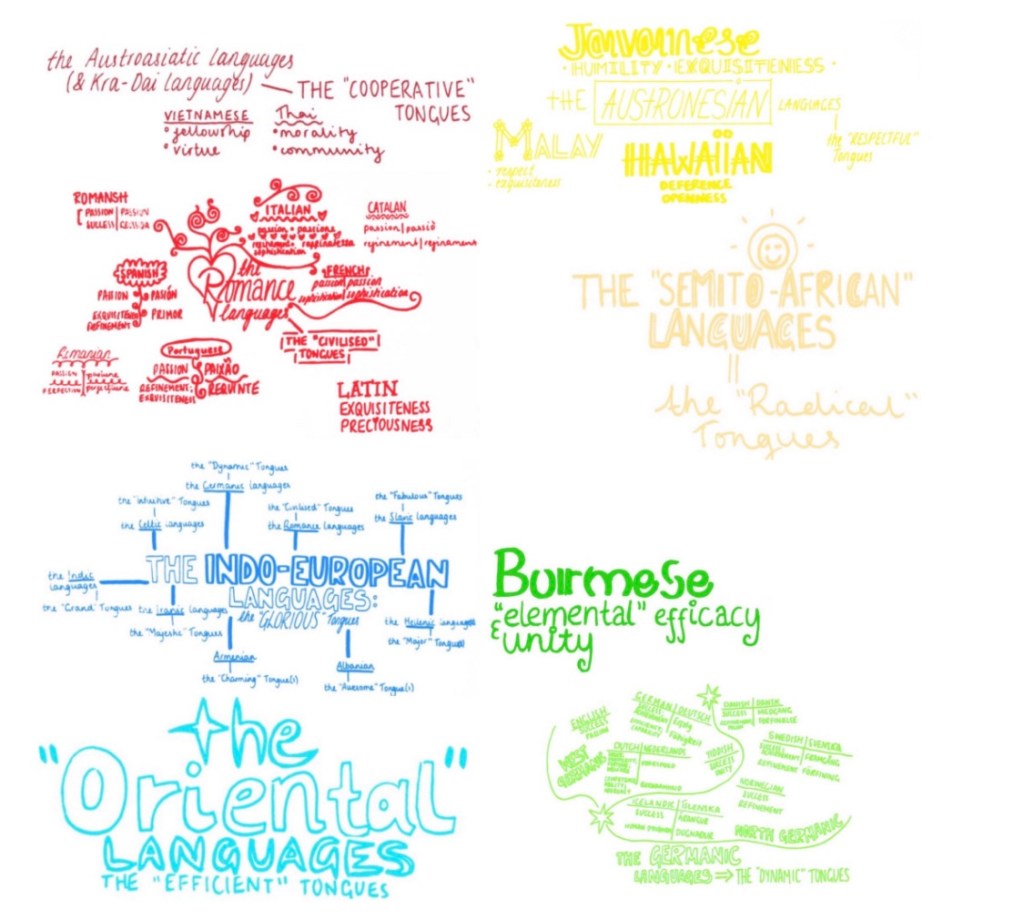

It has been a few years now since I first proposed my Nostratic language family, spoken across the world’s white-Caucasian population. I preliminarily labelled it as the “Transcendent” Tongues in order to capture broadly its characteristics without the formal knowledge of each branch. Thus far, I have laid out three branches, named somewhat playfully before we get to know more details:

• Trumping-Indo-European

• MegaQuirky/Alarodian

• North Picene?

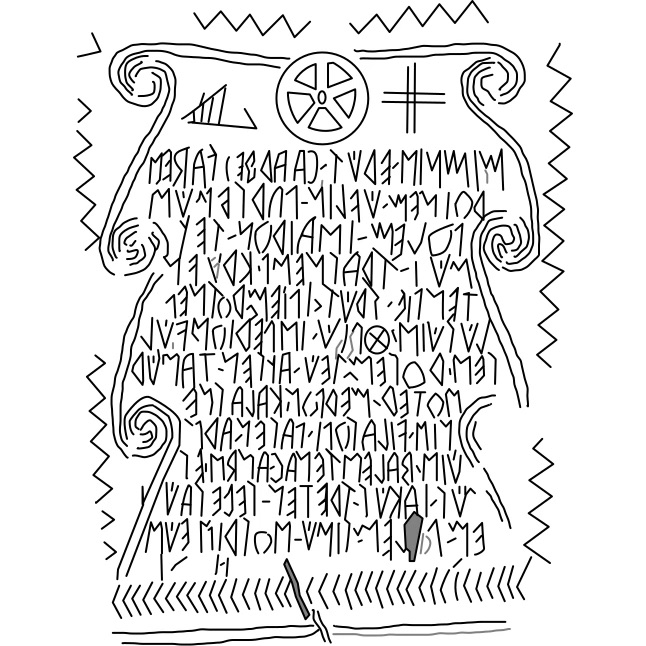

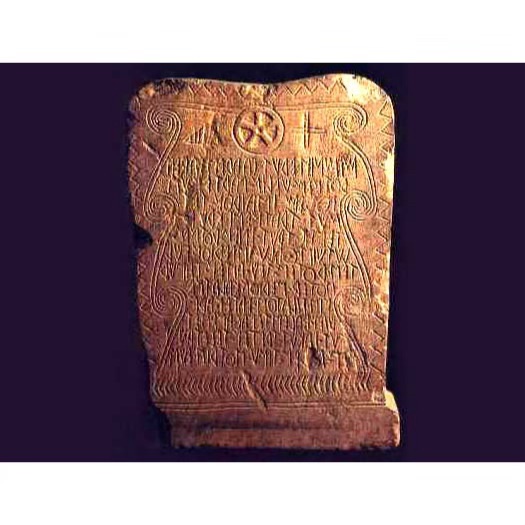

The largely unclassified North Picene language of ancient Italy is a possible hoax and may never have existed, but there are stelae in existence, including the main Novilara stele, dated to the 1st millennium BCE, that feature an unknown language; North Picene is very different from South Picene, which is an Italic language, much more closely related to Italian and Latin. The Picentes or Piceni lived between the Apennines to the west and the Adriatic coast to the east (Picenum). The original Picenes may have spoken unclassified non-Italic language and then become italicised, giving rise to South Picene. North Picene may have belonged to a unique branch of my proposed Nostratic family. No relationships have been identified from any similar vocabulary, if the language existed at all. If it is a hoax, it still represents a good attempt at imagining a new type of Nostratic language. It is testament to the fact that many philologists and language experts have been sort of wrong about what it means for one language to be related to another, beyond lexical similarities, broad ideology also being a very important factor and feature. Picenes worshipped the woodpecker as a sacred animal: picus means a woodpecker in Latin. Either way, hoax or no, the artefacts are surely conservations of vital intelligence about European heritage: yes, North Picene morphology was developed to mirror the way Europe has developed in faithful accordance with language relativity since the Cro-Magnons, at the very least. In Europe, we have always loved binary opposition more than the rest of the world, which was proposed by Ferdinand de Saussure. It has been suggested that proposed phonological evidence links North Picene to Indo-European -allegedly more closely than to, for example, Etruscan-, which may in turn be evidence of its Nostratic identity.

It’s good to lay out the premise of European culture, with us loving binary opposition more than the rest of the world, preserved via North Picene, as we delve into Caucasian history.

mimniś erút gaareśtadeś

rotnem úvlin partenúś

polem iśairon tet

śút tratneši krúviś

tenag trút ipiem rotneš

lútúiś θalú iśperion vúl

teś rotem teú aiten tašúr

śoter merpon kalatne

niś vilatoś paten arn

úiś baleśtenag andś et

šút iakút treten teletaú

nem polem tišú śotriś eúś

The Nostratic language family probably originated around the Caucasus, judging by the continuous coexistence of MegaQuirky languages and Indo-European languages in the area. It may have been instigated by Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers, their predecessors, or relatives. For me the likely place of origin is CHGs the Caucasus, near to where the Indo-European languages were created 5-10,000 years later; the Nostratic language family was probably instituted around 10-20,000 years ago. Caucasus hunter-gatherers supposedly diverged from their common ancestors with Anatolian hunter-gatherers around 25,000 years ago, probably some time after their split from darker skinned Western hunter-gatherers.

The first branch of Nostratic I propose…

… is what I call “Trumping-Indo-European”. The Indo-European languages are widely accepted to constitute the world’s most spoken language family, with billions of speakers. Today, they can be understood informally as the “Glorious” Tongues, a label which should be very helpful in illustrating what sets them apart. The currently spoken commonly accepted branches are: Albanoid, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, Italic. As you might have seen above, I have proposed three overarching branches that lie above those which are currently commonly accepted: Western/Centum, Eastern/Satem, Groundbreaking/Anatolian-Tocharian. Scholars stopped believing in the existence of a Centum/Satem genealogical division within Indo-European at the turn of the 20th century. This happened upon Anatolian and Tocharian being discovered, which are not really Centum nor Satem, and a lack of further obvious evidence that the Centum/Satem division was nothing more than a typological quirk. I wish I could reignite the conversation about bigger overarching primary branches of Indo-European. I think that the Centum/Satem division is geneaological, but messy. Messy because Indo-European branches diverged initially on a mere dialectal basis: they were all very proud of their Indo-European identity. The trajectory of Indo-European language diversification has also not been so streamlined and clean: different groups have been in contact and mixed in different ways over the past 10,000 years, meaning that exchanges have been made which blur the lines between Centum and Satem. Yet language genealogy is not just about the obvious things to study, i.e. lexicology/semiosis, morphology, phonology… and ideology -yep, very important actually- is critical too. For example, Nostratic languages can be easily identified with their a) sophisticated and well-developed lexicology; b) acutely refined, structured, robust morphology; c) smooth and refined phonology, and their d) ambitious, upward-looking ideologies. It’s a shame that it’s too abstract for many people, because the field of philology and comparative linguistics has been stunted. So the genetic division between Western/Centum, Eastern/Satem and Groundbreaking/Anatolian-Tocharian is still there/was still there when Anatolian-Tocharian was still spoken.

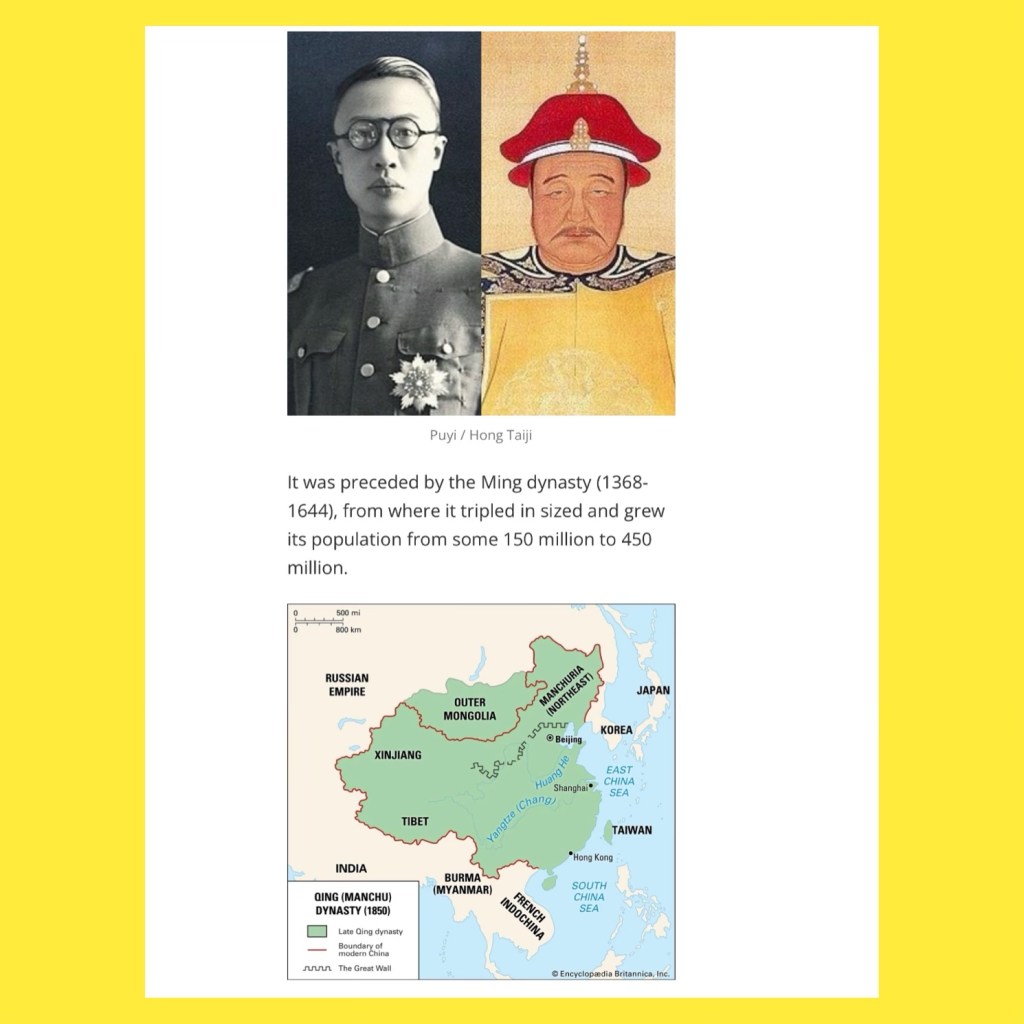

The name Nostratic derives from the Latin word nostrās, meaning ‘our fellow-countryman’ (plural: nostrates). A so-called “Nostratic” grouping was first proposed by Holger Pedersen in 1903, who proposed a common ancestor for the Indo-European, Finno-Ugric, Samoyed, Turkish, Mongolian, Manchu, Yukaghir, Eskimo, Semitic, and Hamitic languages, with the door left open to the inclusion of others in due course. Since Pedersen, “Nostratic” has been defined as those language families that are related to Indo-European – meaning that the grouping centres around Indo-European, which I corroborate. According to Allan Bomhard, Proto-Nostratic would have been spoken between 15,000 and 12,000 BCE, during the Epipaleolithic period, near the end of the last glacial period, perhaps in or nearby the Fertile Crescent. My grouping streamlines the matter somewhat, cutting out Altaic which I don’t believe exists as a language family, also doing away with Afroasiatic and Dravidian – and incorporating minority groupings including Vasconic and Tyrsenian as listed above. I chose the name Nostratic as I think people adhering to the proposal are on the right track – having discerned the existence of the real family at least somewhat faithfully as far as transcendent ideology is concerned.

Beyond Indo-European, I have detected the existence of an important precursor to the world’s most spoken language family commonly recognised today: “Trumpophonism“…

Back in the prehistoric Caucasus, or perhaps somewhere between the Caucasus and the Fertile Crescent, there was disagreement about the “artistic direction”, let’s say, of the relatively newly established Nostratic language family. People to the north developed the habit of riffing on the cultural vision of the tribes to the north of the Caucasus (Sidelkino ancestry supposedly emerged around 14,000 years ago but it’s hard to say exactly who these mysterious inspirational northerners were). Yes, within the early Nostratic (not necessarily still Proto-Nostratic) population, those to the north developed the habit of riffing on the tribes to the north of them. Unfortunately, it irked those the south and they became resentful, leading to the aforementioned disagreement about the direction of Nostratic culture. The southerners were more interested in Anatolia, Iran, South Asia, and the recent establishment of the… MegaQuirky/Alarodian languages, which also entailed the development of the original prestiged “h*rniness“, let’s say. The Alarodian branch includes the likes of: Uralic (Hungarian, Estonian, Finnish), Vasconic (Basque), Tyrsenian/Tyrrhenian (Etruscan), Minoan, Kartvelian/South Caucasian (Georgian), North Caucasian, Hurro-Urartian, Sumerian, Pre-Nuragic Sardinian. The Proto-Alarodians were either Anatolian hunter-gatherers with small additional ancestry from Proto-Nostratic people or maybe more of a mix between AHGs and Proto-Nostratics.

The resentful southerners had the edge of power to wield, and forbade their northern counterparts from proceeding thus. The Nostratic northerners may even have been entertaining interests in diverging and/or getting other ethnic groups wound up about a directional vision the southerners disagreed with. There could have been a war, though of course we cannot really ascertain. Regardless, the southerners ridiculed, shamed, intimidated and eclipsed their northern Nostratic counterparts in whatever way to erase their distinct aspirations. This was the beginning of modern warmongering, or simply cultural malevolence, as we know it today. At some point, this shift gave rise to a new type of Nostratic language: Trumping. These people weren’t very nice in the grand scheme of things, with edgy attitudes towards stature especially, and were of course known for what they did with the tradition of cultural malevolence – however extreme it became, there was certainly at least a culture of psychological torment and warping views. They liked to see themselves as superior, and used their language to distinguish themselves as such, by “trumping” outsiders and even each other. Years later, Indo-European itself would subsequently emerge from the Trumpophone tradition.

What more we can we learn from it?